John D. Dingell, legendary former dean of the House, dies

Michigan Democrat’s 60-year tenure was longest in Congress

By DAVID HAWKINGS and NIELS LESNIEWSKI

John D. Dingell, the longest-serving member of Congress in American history and easily the most overpoweringly influential House committee chairman in the final decades of the last century, died Thursday. He was 92 years old.

“He was a lion of the United States Congress and a loving son, father, husband, grandfather, and friend. He will be remembered for his decades of public service to the people of Southeast Michigan, his razor sharp wit, and a lifetime of dedication to improving the lives of all who walk this earth,” read a statement from the office of Rep. Debbie Dingell, his wife and successor in the House.

The statement said that Dingell “died peacefully” at his home in Dearborn.

The current congresswoman missed President Donald Trump’s State of the Union address on Tuesday, saying that she was home with her husband as they “entered a new phase.”

Speaker Nancy Pelosi described Dingell as “a beloved pillar of the Congress and one of the greatest legislators in American history” in a statement Thursday night.

“Every chapter of Chairman John Dingell’s life has been lived in service to our country, from his time as a House Page, to his service in the Army during World War II, to his almost six decades serving the people of Michigan in the U.S. Congress,” Pelosi said. “John Dingell leaves a towering legacy of unshakable strength, boundless energy and transformative leadership.”

Dingell was a complex and cunning Democrat who represented the Detroit area for 59 years and 21 days — he retired at the end of 2014.

The imposing way he carried his 6-foot-3 frame always made him appear among the largest figures at the Capitol. But he made his most emphatic mark at the Energy and Commerce Committee, where he exercised unequaled power during his 16 years with the gavel and as the senior member of the Democratic minority for a dozen years more.

Although he was deposed from that post in 2008, the successes he enjoyed in the previous three decades have rarely been rivaled in congressional history.

“One of the most influential legislators of all time,” President Barack Obama said in a tribute when Dingell announced he would not run for a 30th re-election.

Obama noted Dingell’s central roles in writing the original Clean Air Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Endangered Species Act, but he paid special tribute to the most prominent cause they shared — medical insurance coverage for all.

(Dingell presided over the House when it cleared the law creating Medicare in 1965 and sat next to Obama at the health care overhaul signing ceremony in 2010. He had proposed “single payer” universal coverage legislation in every Congress until that point, but professed himself satisfied with the measure enacted.)

He came to be known to an entirely new generation thanks to his engagement in social media late in life, becoming among the most active lawmakers on Twitter.

Frequent topics included political and sports commentary, including about the futility of the Detroit Lions NFL team.

“Feeling old because you remember when Pluto was a planet back when you were younger?” he tweeted in 2015. “I was born before they even discovered the darn thing.”

From the outset of his chairmanship in 1981, Dingell was known as a legislative strategist and political tactician with the capacity to mold broad bipartisan coalitions to his will — though rarely without a fair amount of bruising.

His style was to be collaborative in the early stages of legislative bargaining, then clamp down as inflexible once he’d declared his position was settled. Even his allies viewed him as uncommonly stubborn, vindictive and bullying for someone with so much guaranteed authority — and with a self-confidence bordering on arrogance, to boot.

In short, his loud voice, heavy gavel and strong opinions made him an exemplar of the domineering chairman just as that type of Old Bull leader was otherwise nearing extinction.

And he paired all that with a reputation for ruthless accretion of power, with much of the effort spent amassing and then protecting the broadest committee fiefdom any chairmen had enjoyed in the postwar era. In its heyday, Energy and Commerce had most if not all control over bills shaping energy, environmental, health, telecommunications, transportation, financial services and consumer protection policy.

Efforts by his colleagues to so much as chip away at that jurisdiction were repelled with merciless force and a watchful eye ever after. He once said he’d adopted the aphorism the Corleone family made famous in “The Godfather, Part II”: “Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer.”

With as many as 100 aides working for the Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee he also chaired, Dingell would send a seemingly constant stream of letters demanding explanations and information from agencies big and small. When the answers to these “Dingell-grams” were not fast or thorough enough to suit him, he’d quickly dispatch subpoenas and schedule a hearing.

The breadth and persistence of these inquiries continued between 1995 and 2006, when he was ranking minority member, prompting President George W. Bush to once describe Dingell to his face as the “biggest pain in the ass” on Capitol Hill.

Adding to his mystique as a merciless competitor was his collection of stuffed fish and game trophies on the walls of his Rayburn Building office, including that of a 500-pound boar he reportedly felled with only a pistol.

“He will be remembered as one of the most influential members of Congress not to have served as president,” predicted Rep. Joe L. Barton of Texas, who was ranking Energy and Commerce Republican during Dingell’s final term as chairman, in 2007 and 2008.

John David Dingell, Jr. was born on July 8, 1926, in Colorado Springs, Colo., where his father was seeking treatment for tuberculosis. The elder Dingell, a meat salesman and labor organizer, later changed the family surname from Dzieglewicz and moved his family to Capitol Hill after winning in a newly created Detroit congressional district in the 1932 Franklin D. Roosevelt landslide.

The son made his first visit to the House floor before his seventh birthday and spent five of his teenage years as a House page, a time highlighted for him by shooting rats in the Capitol basement with an air gun and being in the chamber for FDR’s “Infamy Speech” after Pearl Harbor.

Less than three years later, Dingell joined the Army. His unit of 210 soldiers was nearly obliterated in the Battle of the Bulge, but Dingell was hospitalized with meningitis during the fighting and so was among the 10 survivors. Discharged in 1945, he earned undergraduate and law degrees from Georgetown, spending most summers as a park ranger.

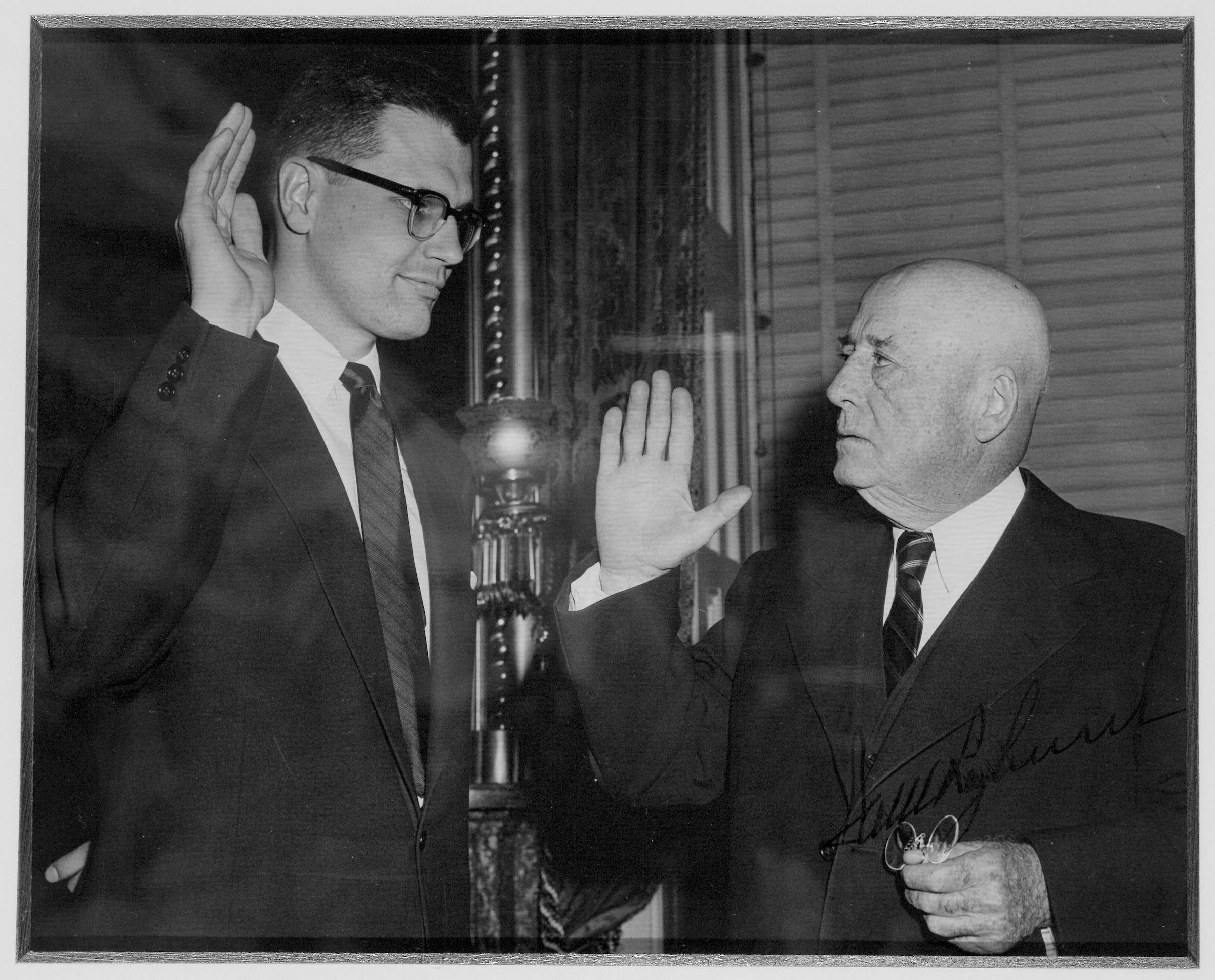

The younger Dingell was an assistant county prosecutor in Dearborn when his father died during a routine physical. He secured organized labor’s backing in a 12-person primary and then took 76 percent in a December 1955 special election to become — at 29 — the youngest member of the 83rd Congress.

He became the longest-serving House member ever in February 2009 (surpassing the record that Mississippi Democrat Jamie L. Whitten set in the early 1990s) and the longest-tenured member in the history of Congress on June 7, 2013 (surpassing Democratic Sen. Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia, who died in office in 2010).

At his retirement, when he was 88, Dingell had been the longest-serving incumbent House member for fully two decades. (In his final terms he often moved through the Capitol on a motorized scooter with a faux vanity license plate of “The Dean.”)

“Presidents come and presidents go,” President Bill Clinton said in 2005 when the congressman celebrated half a century in office. “John Dingell goes on forever.”

Dingell drew less than 60 percent of the vote in a general election only twice: in 1994 and 2010, both years in which Republicans took control of the House from the Democrats.

His toughest races were the two times he was forced by redistricting to face another incumbent Democrat in a primary. After his district was redrawn to be a third African-American, he won in 1964 in part because he’d voted for the Civil Rights Act that year while his opponent, Rep. John Lesinski, had voted no.

Much tougher was his campaign in 2002 against eight-year veteran Rep. Lynn Rivers. That became an intense fight between the very liberal and not-quite-as-liberal factions of the Democratic caucus — and caused a break between Dingell and Nancy Pelosi that proved a decisive downward turning point for his time as a power player.

With the backing of the California Democrat, then the minority whip, Rivers raised significant sums from environmentalists, gun control advocates and supporters of abortion rights — the three communities in the Democratic base with which Dingell had disagreed most prominently.

Dingell had the support of National Rifle Association members and the auto industry and won with 59 percent. But his rift with Pelosi was never repaired, and soon enough she was positioned to help secure an equally consequential Dingell defeat.

Because of his uncompromising interest in protecting Michigan’s automobile industry, Dingell had long been at odds on energy and pollution policies with the more liberal members of his caucus — Pelosi and fellow Californian Henry A. Waxman principal among them. After her first term as speaker, in which Pelosi and Dingell clashed publicly on several fronts, she got behind Waxman’s challenge to the venerated seniority system. In 2008, Waxman wrested the gavel away from the dean on a 137-122 vote of all House Democrats.

Dingell’s unsurpassed presence on Capitol Hill was an essential part of his story, in part because he represented the longest link in the string of family members who have now held the same seat for generations.

Not only did his father occupy it before him for 23 years, but Debbie Dingell had little trouble winning election when her husband retired — becoming the first person to ever come to Congress as the successor to a living spouse.

Lindsey McPherson contributed to this story.